This is the third and final part in our series of posts explaining how to correctly use and understand the apostrophe in English. This post examines some more specialist uses of the apostrophe, especially in literary, phonetic, and older English, and may be of particular interest to non-native speakers who wish to improve their knowledge of classic English literature, and native speakers with similar goals. Readers of modern texts or literature may also find the explanation given in the first point useful, as we have aimed to briefly explain how the apostrophe is commonly used to give a (partial) phonetic representation of spoken English where it differs from the written variety.

Part 1 / Parte 1

Part 2 / Parte 2

1. Non-standard speech

|

| OUR war will be won when "ain't" gets an apostrophe too! |

The apostrophe is also commonly used in written English in order to aid the phonetic representation of non-standard speech forms such as regional dialects, slang, and "incorrect" English, etc.

Often these non-standard forms are contractions (and therefore formed in the same way as more commonplace contractions) sometimes they may only appear to standard speakers as contractions and are thus apostrophised according to standard convention, and sometimes the apostrophe is simply used to indicate pronunciation more clearly to standard speakers.

Such words may have multiple apostrophes; each apostrophe indicates where a speaker of standard English would consider sounds or letters to be omitted. Common examples of words of this sort include:

Ain't = non-standard contraction for am not, have not, will not, etc

'ave = Have, pronounced with silent initial "h"

'e = He, pronounced with silent initial "h"

Goin' = Going, pronounced with silent "g"

'tain't / tain't = Contraction for it ain't

Pronunciation is according to phonetic English norms. Therefore, if you encounter an unfamiliar word of this type, it is likely that you will find it easier to pronounce correctly (as the author intended) than to understand. It is likely that any word encountered in modern English text which contains one or more apostrophes but which cannot be found in a good dictionary is such a non-standard word, which the writer is trying to show phonetically. (Some of the more popular words of this type, however, such as "ain't", are usually to be found in the dictionaries).

Due to the difficulty of applying any sort of rules consistently to non-standard expressions (besides those of pronunciation), I would not recommend that any non-native speaker, unless completely fluent and familiar with the expressions in question, attempts to use them in their own writing. However, this usage is nevertheless something that you may find it helpful to be aware of, for it can be confusing to non-native speakers.

2. Literary contractions

|

| Suggestions are always welcome. |

Through established literary convention and familiarity, these artificial words have survived the decline of traditional poetry in English and may be encountered in modern poetry and prose. Modern native speakers may use words of this type when they wish to appear erudite or "poetic", or wish to give their writing a quaint or antiquated flavor. A few typical examples; when encountered these are pronounced as spelled, not as the usual full version of the word would be:

E'en = Even

O'er = Over

Th' = The (due to having essentially no syllables due to the removal of the vowel, this is usually joined to the following word)

'Gan = Began

Older poets in English commonly use this technique with a much wider range of words than modern writers, and often coined their own usages, using the apostrophe to show that the word had a particular pronunciation that may be different to the usual one, for example:

Whisp'ring = Whispering, pronounced with two syllables instead of three

Fev'rous = Feverous (in a state of fever) pronounced again with two syllables instead of three

Orat'ries = Oratories (again, a three-syllable word shortened to two)

Certain words like " 'twas " (a contraction for "it was") and " 'tis" (a contraction for it is) which were once everyday speech, would now be regarded more as literary contractions, as these contractions have largely gone out of use in modern spoken English and are encountered by most people in pre-20th Century literature.

Modern practice is generally not a good guide to the correct use of

the words I have discussed in this part of the post (often called "Poeticisms" in English, though this term also

has a wider application).

It is common for amateur poets in modern

times (or those who are trying to give their writing a more "literary"

feel without possessing the requisite knowledge) to use words of this

type quite erratically in the hope that it will give a more antiquated

and sophisticated flavour to their writing. Unfortunately, most of the

time they only succeed in looking ridiculous to better-informed readers!

3. Word endings

A minor additional point: in older varieties of English, mainly in English written before the beginning of the 20th century, it was common practice to form certain word endings, particularly the -ed used for the past tense of many verbs, with an apostrophe. This apostrophe is not normally now used except to give a quaint "old fashioned" flavor to writing; the pronunciation and spelling of these words is otherwise normally identical to their modern equivalents.

Happen´d = Happened

Forc´d = Forced

Look'd = Looked

Stol'n = Often used for "Stolen", and appears to show the word being pronounced with one syllable rather than the modern two. It may also be at times a speech or literary contraction, as described above.

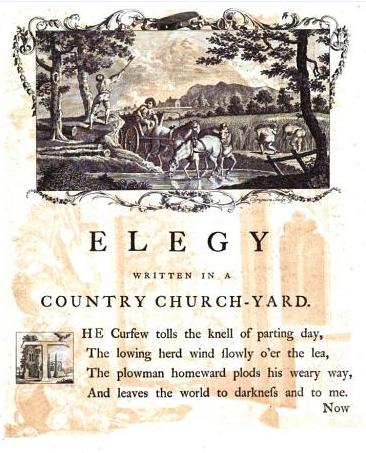

|

| Knowing the apostrophe is just one part of understanding classic literature. Good luck with the rest! My husband took at least 5 minutes explaining to me what the verse above meant. |

Esta é a terceira e última parte da nossa série de posts que explicam como usar corretamente e entender o apóstrofo em inglês. Este post examina um pouco mais os usos especiais do apóstrofe, especialmente em inglês literário, fonético, e mais antigo, e pode ser interessante a falantes não-nativos que desejam melhorar o seu conhecimento da literatura inglesa clássica, e falantes nativos com objetivos semelhantes. Os leitores de textos modernos ou literatura também podem achar a explicação dada no primeiro ponto útil, como aspiramos a explicar resumidamente como o apóstrofo é comumente usado para dar uma representação fonética (parcial) do inglês dito onde ele se diferencia da versão escrita.

1. Discurso não-padrão

O apóstrofo também é comumente usado no inglês escrito para ajudar a representação fonética de formas de discurso não-padrão como dialetos regionais, gíria, inglês "incorreto", etc.

Muitas vezes essas formas fora do padrão são contrações (e por isso se formaram do mesmo modo que outras contrações comuns) às vezes eles podem aparecer a falantes padrão como contrações e são dessa forma, utilizados apóstrofos, segundo a convenção padrão, e às vezes o apóstrofe é simplesmente usado para indicar a pronúncia mais claramente a falantes padrão.

Tais palavras podem ter múltiplos apóstrofos; cada apóstrofo indica onde um falante do inglês padrão consideraria que sons ou letras foram omissos. Os exemplos comuns de palavras deste tipo incluem:

Ain`t = contração não padrão de "am not, have not, will not", etc.

'ave = "have" pronunciado com o h inicial silencioso

'e = "he" pronunciado com o h inicial silencioso

Goin' = Going, pronunciado com "g" silencioso

'tain't / tain't = Contração para "it ain't"

A pronúncia segue as normas fonéticas inglesas. Por isso, se você encontrar uma palavra pouco conhecida desse tipo, é provável que você achará mais fácil pronunciar corretamente (como o autor pretendeu) do que entendê-la. É provável que qualquer palavra encontrada em textos em inglês moderno que contém um ou vários apóstrofos mas que não pode ser encontrado em um bom dicionário é uma palavra tão fora do padrão, que o escritor está tentando a mostrar foneticamente (algumas palavras mais populares deste tipo, contudo, como "ain't", devem ser normalmente encontrados nos dicionários).

Devido à dificuldade para aplicar qualquer tipo de regras constantemente a expressões não-padrões (além daquelas da pronúncia), eu não recomendaria que qualquer falante não-nativo, a menos que completamente fluente e familiar com as expressões em questão, tente usá-los na sua própria escrita. Contudo, este uso é algo que você pode achar útil saber, já que pode ser confuso a falantes não-nativos.

2. Contrações literárias

O inglês literário tem um uso mais especializado do apóstrofo, que é útil para alguém que estuda ou lê pelo o prazer a literatura inglesa tradicional. Aqui o apóstrofo não indica letras que são naturalmente elididas no discurso casual, mas onde as letras são retiradas para encurtar artificialmente uma palavra quando é dita em voz alta. A razão original de fazer isto foi permitir a palavras certas comumente usadas serem pronunciadas com menos sílabas do que o habitual, que permitiram a escritores mais flexibilidade na prova dessas palavras à métrica poéticas formal e tradicional.

Por convenção literária estabelecida e familiaridade, essas palavras artificiais sobreviveram ao declínio da poesia tradicional em inglês e podem ser encontradas em poesia moderna e prosa. Os falantes nativos modernos podem usar palavras deste tipo quando eles desejam parecer eruditos ou "poéticos", ou para dar a sua escrita um sabor singular ou antiquado. Alguns exemplos típicos, quando encontrados, são pronunciados da mesma forma que soletrados, não como a versão cheia habitual da palavra:

Devido à dificuldade para aplicar qualquer tipo de regras constantemente a expressões não-padrões (além daquelas da pronúncia), eu não recomendaria que qualquer falante não-nativo, a menos que completamente fluente e familiar com as expressões em questão, tente usá-los na sua própria escrita. Contudo, este uso é algo que você pode achar útil saber, já que pode ser confuso a falantes não-nativos.

2. Contrações literárias

O inglês literário tem um uso mais especializado do apóstrofo, que é útil para alguém que estuda ou lê pelo o prazer a literatura inglesa tradicional. Aqui o apóstrofo não indica letras que são naturalmente elididas no discurso casual, mas onde as letras são retiradas para encurtar artificialmente uma palavra quando é dita em voz alta. A razão original de fazer isto foi permitir a palavras certas comumente usadas serem pronunciadas com menos sílabas do que o habitual, que permitiram a escritores mais flexibilidade na prova dessas palavras à métrica poéticas formal e tradicional.

Por convenção literária estabelecida e familiaridade, essas palavras artificiais sobreviveram ao declínio da poesia tradicional em inglês e podem ser encontradas em poesia moderna e prosa. Os falantes nativos modernos podem usar palavras deste tipo quando eles desejam parecer eruditos ou "poéticos", ou para dar a sua escrita um sabor singular ou antiquado. Alguns exemplos típicos, quando encontrados, são pronunciados da mesma forma que soletrados, não como a versão cheia habitual da palavra:

E'en = Even

O'er = Over

Th' = The (já que essencialmente não tem sílabas devido à retirada da vogal, normalmente é combinada com a palavra seguinte)

'Gan = Began

Poetas mais antigos normalmente usam essa técnica muito mais que escritores modernos, e normalmente inventam seu jeito, usando o apóstrofo para mostrar que a palavra tinha uma determinada pronuncia diferente da usual, por exemplo:

Poetas mais antigos normalmente usam essa técnica muito mais que escritores modernos, e normalmente inventam seu jeito, usando o apóstrofo para mostrar que a palavra tinha uma determinada pronuncia diferente da usual, por exemplo:

Whisp'ring = Whispering, pronunciada com duas sílabas ao invés de três

Fev'rous = Feverous pronunciada de novo com duas sílabas ao invés de três

Orat'ries = Oratories (a mesma coisa)

Certas palavras como "'twas" (uma contração de "it was") e "tis" (uma contração para "it is") que foram no passado discurso usual, seriam consideradas agora mais como contrações literárias, como essas contrações basicamente sairam do uso em inglês dito moderno e são encontradas pela maior parte de pessoas na literatura anterior ao século 20.

A prática moderna não é geralmente uma boa guia para o uso correto das palavras que discutimos nesta parte do post (muitas vezes chamada "Poeticisms" em inglês, embora este termo também tenha uma aplicação mais larga).

É comum para poetas amadores em tempos modernos (ou aqueles que estão tentando dar a sua escrita uma sensação "mais literária" sem possuir o conhecimento requerido) usar as palavras deste tipo bastante irregularmente na esperança que ele dará um sabor mais antiquado e sofisticado à sua escrita. Infelizmente, a maior parte do tempo eles só têm sucesso em parecerem ridículos para leitores melhor informados!

3. Finais de palavras

Um ponto adicional de menor relevância: em variedades mais antigas do inglês, principalmente em inglês escrito antes do começo do século 20, foi a prática comum formar certos finais de palavra, em particular o - ed usado para o passado de muitos verbos, com um apóstrofo. Este apóstrofo não é usado normalmente hoje em dia exceto para dar um sabor antigo à escrita; a pronúncia e a ortografia dessas palavras são normalmente idênticas às suas equivalentes modernas.

Happen´d = Happened

Forc´d = Forced

Look'd = Looked

Stol'n = Muitas vezes usado para "Stolen", e parece mostrar a palavra pronunciada com uma sílaba e não duas. Também pode estar de vez em quando em um discurso ou contração literária, como ja foi descrito.

Certas palavras como "'twas" (uma contração de "it was") e "tis" (uma contração para "it is") que foram no passado discurso usual, seriam consideradas agora mais como contrações literárias, como essas contrações basicamente sairam do uso em inglês dito moderno e são encontradas pela maior parte de pessoas na literatura anterior ao século 20.

A prática moderna não é geralmente uma boa guia para o uso correto das palavras que discutimos nesta parte do post (muitas vezes chamada "Poeticisms" em inglês, embora este termo também tenha uma aplicação mais larga).

É comum para poetas amadores em tempos modernos (ou aqueles que estão tentando dar a sua escrita uma sensação "mais literária" sem possuir o conhecimento requerido) usar as palavras deste tipo bastante irregularmente na esperança que ele dará um sabor mais antiquado e sofisticado à sua escrita. Infelizmente, a maior parte do tempo eles só têm sucesso em parecerem ridículos para leitores melhor informados!

3. Finais de palavras

Um ponto adicional de menor relevância: em variedades mais antigas do inglês, principalmente em inglês escrito antes do começo do século 20, foi a prática comum formar certos finais de palavra, em particular o - ed usado para o passado de muitos verbos, com um apóstrofo. Este apóstrofo não é usado normalmente hoje em dia exceto para dar um sabor antigo à escrita; a pronúncia e a ortografia dessas palavras são normalmente idênticas às suas equivalentes modernas.

Happen´d = Happened

Forc´d = Forced

Look'd = Looked

Stol'n = Muitas vezes usado para "Stolen", e parece mostrar a palavra pronunciada com uma sílaba e não duas. Também pode estar de vez em quando em um discurso ou contração literária, como ja foi descrito.